168P/Hergenrother

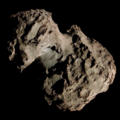

168P/Hergenrother during its 2012 outburst as imaged from the Mount Lemmon Observatory | |

| Discovery[1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Carl W. Hergenrother |

| Discovery site | Catalina Sky Survey |

| Discovery date | 22 November 1998 |

| Designations | |

| P/1998 W2 P/2005 N2 | |

| Orbital characteristics[2][3] | |

| Epoch | 25 February 2023 (JD 2460000.5) |

| Observation arc | 21.12 years |

| Earliest precovery date | 21 November 1998 |

| Number of observations | 3,631 |

| Aphelion | 5.817 AU |

| Perihelion | 1.357 AU |

| Semi-major axis | 3.587 AU |

| Eccentricity | 0.62169 |

| Orbital period | 6.794 years |

| Inclination | 21.615° |

| 355.43° | |

| Argument of periapsis | 15.041° |

| Mean anomaly | 188.01° |

| Last perihelion | 5 August 2019 |

| Next perihelion | 18 May 2026 |

| TJupiter | 2.663 |

| Earth MOID | 0.420 AU |

| Jupiter MOID | 0.001 AU |

| Physical characteristics[2][4] | |

Mean diameter | 0.91 km (0.57 mi) |

| Comet total magnitude (M1) | 7.0 |

| Comet nuclear magnitude (M2) | 15.2 |

| 8.0 (2012 apparition) | |

168P/Hergenrother is a periodic comet in the Solar System. The comet originally named P/1998 W2 returned in 2005 and got the temporary name P/2005 N2.[5] The comet was last observed in January 2020[3] and may have continued fragmenting after the 2012 outburst.

Observational history

[edit]Discovery

[edit]On 22 November 1998, Carl W. Hergenrother spotted a new comet from CCD images taken by Timothy B. Spahr a day earlier with the Catalina Sky Survey's 0.41 m (16 in) telescope.[6] Preliminary orbital calculations by Brian G. Marsden reveal that the comet has a periodic orbit of 6.78 years.[1] At the time, the comet was a 17th-magnitude object within the constellation Ursa Minor.[a]

Between 2000 and 2002, Kazuo Kinoshita and Shuichi Nakano independently used the comet's positions during its 1998 apparition to predict its next perihelion date, which is around 2 November 2005.[6] It was successfully recovered by Australian astronomer, David Herald, on 6 November 2005.[5]

2012 outburst

[edit]The comet came to perihelion on 1 October 2012,[7] and was expected to reach about apparent magnitude 15.2, but due to an outburst the comet reached apparent magnitude 8.[8] As a result of the outburst of gas and dust, the comet was briefly more than 500 times brighter than it would have been without the outburst.[b] On 19 October, images by the Virtual Telescope Project showed a dust cloud trailing the nucleus.[9] Images by the 2 m (79 in) Faulkes Telescope North on 26 October,[10] confirm a fragmentation event.[11] The secondary fragment was about magnitude 17. Further observations by the 8.1 m (320 in) Gemini telescope show that the comet fragmented into at least four parts in six fragmentation events.[10][12][13]

2019 apparition

[edit]168P came to perihelion on 5 August 2019,[3] when it was 76 degrees from the Sun. It then made a closest approach to Earth on 6 November 2019, when it was 1 AU (150 million km) from Earth with a solar elongation of about 110 degrees. It was not recovered until 3 January 2020, when it was 141 degrees from the Sun, but only two observations on a single night were reported.

Physical characteristics

[edit]Observations conducted by the Spitzer Space Telescope between 2006 and 2007 showed that Hergenrother's nucleus was originally about 0.96 km (0.60 mi) in diameter before it disintegrated on its 2012 outburst.[14] This was later revised to 0.91 km (0.57 mi) upon reanalysis of data in 2020.[4]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c C. W. Hergenrother (23 November 1998). B. G. Marsden (ed.). "Comet C/1998 W2 (Hergenrother)". IAU Circular. 7057.

- ^ a b "168P/Hergenrother – JPL Small-Body Database Lookup". ssd.jpl.nasa.gov. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 1 April 2025.

- ^ a b c "168P/Hergenrother Orbit". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ^ a b M. L. Paradowski (2020). "A New Method of Determining Brightness and Size of Cometary Nuclei" (PDF). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 492 (3): 4175–4188. Bibcode:2020MNRAS.492.4175P. doi:10.1093/mnras/stz3597.

- ^ a b D. Herald (5 July 2005). D. W. Green (ed.). "Comet P/2005 N2 (Hergenrother)". IAU Circular. 8560.

- ^ a b G. W. Kronk. "168P/Hergenrother". Cometography.com. Retrieved 1 April 2025.

- ^ S. Nakano (23 April 2009). "168P/Hergenrother (NK 1778)". OAA Computing and Minor Planet Sections. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ S. Yoshida (21 February 2012). "168P/Hergenrother (2012)". www.aerith.net. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ G. Masi (19 October 2012). "Comet 168P/Hergenrother: hi-res images (19 Oct. 2012)". Virtual Telescope Project. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ a b D. C. Agle (2 November 2012). "Scientists Monitor Comet Break-up". jpl.nasa.gov. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2012-349. Retrieved 1 April 2025.

- ^ G. Sostero; N. Howes; E. Guido (26 October 2012). "Splitting event in comet 168P/Hergenrother". Remanzacco Observatory in Italy – Comets & Neo. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ P. Plait (5 November 2012). "Breaking up is easy to do. If you're a comet". Bad Astronomy. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ Z. Sekanina (2014). "Temporal Correlation Between Outbursts and Fragmentation Events of Comet 168P/Hergenrother". arXiv:1409.7641 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ Y. R. Fernández; M. S. Kelley; P. L. Lamy; I. Toth; O. Groussin; et al. (2013). "Thermal Properties, Sizes, and Size Distribution of Jupiter-family Cometary Nuclei". Icarus. 226 (1): 1138–1170. arXiv:1307.6191. Bibcode:2013Icar..226.1138F. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2013.07.021.

External links

[edit]- 168P/Hergenrother at the JPL Small-Body Database

- 168P/Hergenrother at the Minor Planet Center

- 168P on Seiichi Yoshida's comet list

- Comet 168P Hergenrother in outburst (Google+ chat archive Oct 12, 2012)

- Comet Hergenrother in Outburst (Carl Hergenrother : 20 Oct 2012)

- Comet 168P and fragment as seen by Kitt Peak WIYN 3.5-metre (140 in) on 30 Oct 2012

![{\displaystyle ({\sqrt[{5}]{100}})^{15.2-8}\approx 758}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b7f0eead17b768506983eda9da2f7d51117084c5)